BY BRUCE AUGENSTEIN

There’s been a certain amount of discussion, in this and other files, about the concepts of horsepower and torque, how they relate to each other, and how they apply in terms of automobile performance. I have observed that, although nearly everyone participating has a passion for automobiles, there is a huge variance in knowledge. It’s clear that a bunch of folks have strong opinions (about this topic, and other things), but that has generally led to more heat than light if you get my drift :-). I’ve posted a subset of this note in another string but felt it deserved to be dealt with as a separate topic. This is meant to be a primer on the subject, which may lead to a serious discussion that fleshes out this and other subtopics that will inevitably need to be addressed. OK. Here’s the deal, in moderately plain English.

Force, Work, and Time

If you have a one-pound weight bolted to the floor, and try to lift it with one pound of force (or 10, or 50 pounds), you will have applied force and exerted energy, but no work will have been done. If you unbolt the weight and apply a force sufficient to lift the weight one foot, then a one-foot pound of work will have been done. If that event takes a minute to accomplish, then you will be doing work at the rate of a one-foot pound per minute. If it takes one second to accomplish the task, then work will be done at the rate of 60 foot-pounds per minute, and so on.

In order to apply these measurements to automobiles and their performance (whether you’re speaking of torque, horsepower, newton meters, watts, or any other terms), you need to address the three variables of force, work, and time.

A while back, a gentleman by the name of Watt (the same gent who did all that neat stuff with steam engines) made some observations and concluded that the average horse of the time could lift a 550-pound weight one foot in one second, thereby performing work at the rate of 550-foot pounds per second, or 33,000-foot pounds per minute, for an eight-hour shift, more or less. He then published those observations and stated that 33,000-foot pounds per minute of work were equivalent to the power of one horse, or, one horsepower.

Everybody else said OK. 🙂

For purposes of this discussion, we need to measure units of force from rotating objects such as crankshafts, so we’ll use terms that define a *twisting* force, such as foot-pounds of torque. A foot pound of torque is the twisting force necessary to support a one-pound weight on a weightless horizontal bar, one foot from the fulcrum.

Now, it’s important to understand that nobody on the planet ever actually measures horsepower from a running engine. What we actually measure (on a dynamometer) is torque, expressed in foot pounds (in the U.S.), and then we *calculate* actual horsepower by converting the twisting force of torque into the work units of horsepower.

Visualize that one-pound weight we mentioned, one foot from the fulcrum on its weightless bar. If we rotate that weight for one full revolution against a one-pound resistance, we have moved it a total of 6.2832 feet (Pi * a two-foot circle), and, incidentally, we have done 6.2832 foot pounds of work.

OK. Remember Watt? He said that 33,000 foot pounds of work per minute was equivalent to one horsepower. If we divide the 6.2832 foot pounds of work we’ve done per revolution of that weight into 33,000 foot pounds, we come up with the fact that one foot pound of torque at 5252 rpm is equal to 33,000 foot pounds per minute of work, and is the equivalent of one horsepower. If we only move that weight at the rate of 2626 rpm, it’s the equivalent of 1/2 horsepower (16,500 foot pounds per minute), and so on. Therefore, the following formula applies for calculating horsepower from a torque measurement:

Torque * RPM

Horsepower = ————5252

This is not a debatable item. It’s the way it’s done. Period.

The Case For Torque

Now, what does all this mean in Carland?

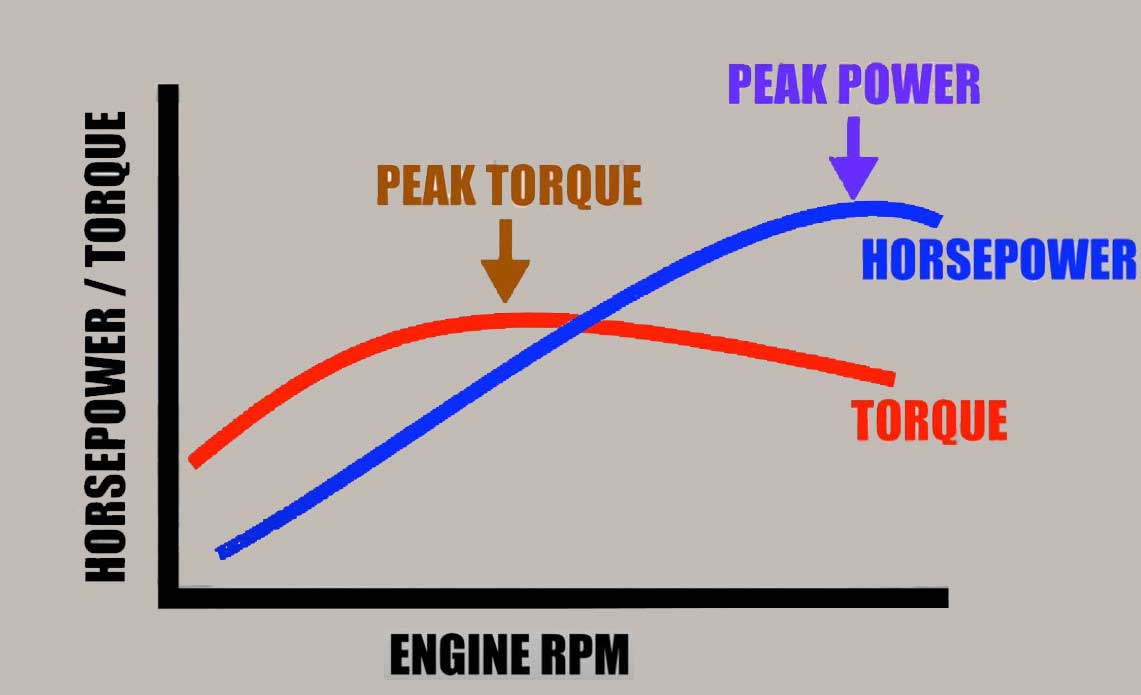

First of all, from a driver’s perspective, torque, to use the vernacular, RULES :-). Any given car, in any given gear, will accelerate at a rate that *exactly* matches its torque curve (allowing for increased air and rolling resistance as speeds climb). Another way of saying this is that a car will accelerate hardest at its torque peak in any given gear, and will not accelerate as hard below that peak, or above it. Torque is the only thing that a driver feels, and horsepower is just sort of an esoteric measurement in that context. 300 foot pounds of torque will accelerate you just as hard at 2000 rpm as it would if you were making that torque at 4000 rpm in the same gear, yet, per the formula, the horsepower would be *double* at 4000 rpm. Therefore, horsepower isn’t particularly meaningful from a driver’s perspective, and the two numbers only get friendly at 5252 rpm, where horsepower and torque always come out the same.

In contrast to a torque curve (and the matching pushback into your seat), horsepower rises rapidly with rpm, especially when torque values are also climbing. Horsepower will continue to climb, however, until well past the torque peak, and will continue to rise as engine speed climbs, until the torque curve really begins to plummet, faster than engine rpm is rising. However, as I said, horsepower has nothing to do with what a driver *feels*.

You don’t believe all this?

Fine. Take your non-turbo car (turbo lag muddles the results) to its torque peak in first gear, and punch it. Notice the belt in the back? Now take it to the power peak, and punch it. Notice that the belt in the back is a bit weaker. Fine. Can we go on, now? 🙂

The Case For Horsepower

OK. If torque is so all-fired important, why do we care about horsepower?

Because (to quote a friend), “It is better to make torque at high rpm than at low rpm, because you can take advantage of *gearing*.

For an extreme example of this, I’ll leave Carland for a moment, and describe a waterwheel I got to watch a while ago. This was a pretty massive wheel (built a couple of hundred years ago), rotating lazily on a shaft that was connected to the works inside a flour mill. Working some things out from what the people in the mill said, I was able to determine that the wheel typically generated about 2600(!) foot pounds of torque. I clocked its speed and determined that it was rotating at about 12 rpm. If we hooked that wheel to, say, the drive wheels of a car, that car would go from zero to twelve rpm in a flash, and the waterwheel would hardly notice :-).

On the other hand, twelve rpm of the drivewheels is around one mph for the average car, and, in order to go faster, we’d need to gear it up. Getting to 60 mph would require gearing the wheel up enough so that it would be effectively making a little over 43 foot pounds of torque at the output, which is not only a relatively small amount, it’s less than what the average car would need in order to actually get to 60. Applying the conversion formula gives us the facts on this. Twelve times twenty-six hundred, over five thousand two hundred fifty-two gives us:

6 HP.

Oops. Now we see the rest of the story. While it’s clearly true that the water wheel can exert a *bunch* of force, its *power* (ability to do work over time) is severely limited.

At The Dragstrip

OK. Back to Carland, and some examples of how horsepower makes a major difference in how fast a car can accelerate, in spite of what torque on your backside tells you :-).

A very good example would be to compare the current LT1 Corvette with the last of the L98 Vettes, built-in 1991. Figures as follows:

Engine Peak HP @ RPM Peak Torque @ RPM

—— ————- —————–

L98 250 @ 4000 340 @ 3200

LT1 300 @ 5000 340 @ 3600

The cars are geared identically, and car weights are within a few pounds, so it’s a good comparison.

First, each car will push you back in the seat (the fun factor) with the same authority – at least at or near peak torque in each gear. One will tend to *feel* about as fast as the other to the driver, but the LT1 will actually be significantly faster than the L98, even though it won’t pull any harder. If we mess about with the formula, we can begin to discover exactly *why* the LT1 is faster. Here’s another slice at that formula:

Horsepower * 5252

Torque = —————–RPM

If we plug some numbers in, we can see that the L98 is making 328 foot pounds of torque at its power peak (250 hp @ 4000), and we can infer that it cannot be making any more than 263 pound feet of torque at 5000 rpm, or it would be making more than 250 hp at that engine speed and would be so rated. In actuality, the L98 is probably making no more than around 210 pound feet or so at 5000 rpm, and anybody who owns one would shift it at around 46-4700 rpm, because more torque is available at the drive wheels in the next gear at that point. On the other hand, the LT1 is fairly happy making 315 pound-feet at 5000 rpm and is happy right up to its mid-5s redline.

So, in a drag race, the cars would launch more or less together. The L98 might have a slight advantage due to its peak torque occurring a little earlier in the rev range, but that is debatable since the LT1 has a wider, flatter curve (again pretty much by definition, looking at the figures). From somewhere in the mid-range and up, however, the LT1 would begin to pull away. Where the L98 has to shift to second (and throw away torque multiplication for speed), the LT1 still has around another 1000 rpm to go in first, and thus begins to widen its lead, more and more as the speeds climb. As long as the revs are high, the LT1, by definition, has an advantage.

Another example would be the LT1 against the ZR-1. Same deal, only in reverse. The ZR-1 actually pulls a little harder than the LT1, although its torque advantage is softened somewhat by its extra weight. The real advantage, however, is that the ZR-1 has another 1500 rpm in hand at the point where the LT1 has to shift.

There are numerous examples of this phenomenon. The Integra GS-R, for instance, is faster than the garden variety Integra, not because it pulls particularly harder (it doesn’t), but because it pulls *longer*. It doesn’t feel particularly faster, but it is.

A final example of this requires your imagination. Figure that we can tweak an LT1 engine so that it still makes peak torque of 340 foot pounds at 3600 rpm, but, instead of the curve dropping off to 315 pound feet at 5000, we extend the torque curve so much that it doesn’t fall off to 315 pound feet until 15000 rpm. OK, so we’d need to have virtually all the moving parts made out of unobtanium :-), and some sort of turbocharging on demand that would make enough high-rpm boost to keep the curve from falling, but hey, bear with me.

If you raced a stock LT1 with this car, they would launch together, but, somewhere around the 60 foot point, the stocker would begin to fade, and would have to grab second gear shortly thereafter. Not long after that, you’d see in your mirror that the stocker has grabbed third, and not too long after that, it would get fourth, but you wouldn’t be able to see that due to the distance between you as you crossed the line, *still in first gear*, and pulling like crazy.

I’ve got a computer simulation that models an LT1 Vette in a quarter-mile pass, and it predicts a 13.38 second ET, at 104.5 mph. That’s pretty close (actually a tiny bit conservative) to what a stock LT1 can do at 100% air density at a high traction drag strip, being powershifted. However, our modified car, while belting the driver in the back no harder than the stocker (at peak torque) does an 11.96, at 135.1 mph, all in first gear, of course. It doesn’t pull any harder, but it sure as hell pulls longer :-). It’s also making *900* hp, at 15,000 rpm.

Of course, folks who are knowledgeable about drag racing are now openly snickering, because they’ve read the preceding paragraph, and it occurs to them that any self-respecting car that can get to 135 mph in a quarter mile will just naturally be doing this in less than ten seconds. Of course, that’s true, but I remind these same folks that any self-respecting engine that propels a Vette into the nines is also making a whole bunch more than 340 foot pounds of torque.

That does bring up another point, though. Essentially, a more “real” Corvette running 135 mph in a quarter mile (maybe a mega big block) might be making 700-800 foot-pounds of torque, and thus it would pull a whole bunch harder than my paper tiger would. It would need slicks and other modifications in order to turn that torque into forwarding motion, but it would also get from here to way over there a bunch quicker.

On the other hand, as long as we’re making quarter-mile passes with fantasy engines, if we put a 10.35:1 final-drive gear (3.45 is stock) in our fantasy LT1, with slicks and other chassis mods, we’d be in the nines just as easily as the big block would, and thus save face :-). The mechanical advantage of such a nonsensical rear gear would allow our combination to pull just as hard as the big block, plus we’d get to do all that gear banging and such that real racers do and finish in fourth gear, as God intends. 🙂

The only modification to the preceding paragraph would be the polar moments of inertia (flywheel effect) argument brought about by such a stiff rear gear, and that argument is outside of the scope of this already massive document. Another time, maybe, if you can stand it :-).

At The Bonneville Salt Flats

Looking at top speed, horsepower wins again, in the sense that making more torque at high rpm means you can use a stiffer gear for any given car speed, and thus have more effective torque *at the drive wheels*.

Finally, operating at the power peak means you are doing the absolute best you can at any given car speed, measuring torque at the drive wheels. I know I said that acceleration follows the torque curve in any given gear, but if you factor in gearing vs car speed, the power peak is *it*. An example, yet again, of the LT1 Vette will illustrate this. If you take it up to its torque peak (3600 rpm) in a gear, it will generate some level of torque (340 foot pounds times whatever overall gearing) at the drive wheels, which is the best it will do in that gear (meaning, that’s where it is pulling hardest in that gear).

However, if you re-gear the car so it is operating at the power peak (5000 rpm) *at the same car speed*, it will deliver more torque to the drive wheels, because you’ll need to gear it up by nearly 39% (5000/3600), while engine torque has only dropped by a little over 7% (315/340). You’ll get a 29% gain in drive wheel torque at the power peak vs the torque peak, at a given car speed.

Any other rpm (other than the power peak) at a given car speed will net you a lower torque value at the drive wheels. This would be true of any car on the planet, so, the theoretical “best” top speed will always occur when a given vehicle is operating at its power peak.

“Modernizing” The 18th Century

OK. For the final-final point (Really. I Promise.), what if we ditched that water wheel, and bolted an LT1 in its place? Now, no LT1 is going to be making over 2600 foot-pounds of torque (except possibly for a single, glorious instant, running on nitromethane), but, assuming we needed 12 rpm for input to the mill, we could run the LT1 at 5000 rpm (where it’s making 315 foot pounds of torque), and gear it down to a 12 rpm output. Result? We’d have over *131,000* foot pounds of torque to play with. We could probably twist the whole flour mill around the input shaft if we needed to :-).

The Only Thing You Really Need to Know

Repeat after me. “It is better to make torque at high rpm than at low rpm because you can take advantage of *gearing*.” 🙂 Thanks for your time.